Abandoned Melbourne author Gavin John reflects on the surreal experience of photographing Melbourne during the 2020 Covid lockdown...

There are people in Japan classified as the Hikikomori. They elect to withdraw from society, living reclusive, predominantly solitary lives, spending much of their time online. In South Korea, the Honjok similarly live out their time alone.

In February 2021, it became clear to me that aspects of both these unconventional existences would almost certainly be enforced upon Melbournians due to a general population lockdown, as a response to the Coronavirus pandemic. I am a photographer normally focussed on the wilderness, capturing wide ranging places across the globe. Enforced immobility would present a challenge to say the least; the notion of being locked down indefinitely was troubling indeed. But I told myself there is almost always an opportunity to turn a negative into a positive.

Although a nature photographer by trade, I have always been a fan of urban exploration photography and have appreciated the work of the past masters of this craft. But rarely have I considered the results of my ventures into street photography anything other than commonplace, and certainly not inventive or original. I like to think this is because I have never approached urban subject matter with the same ardour.

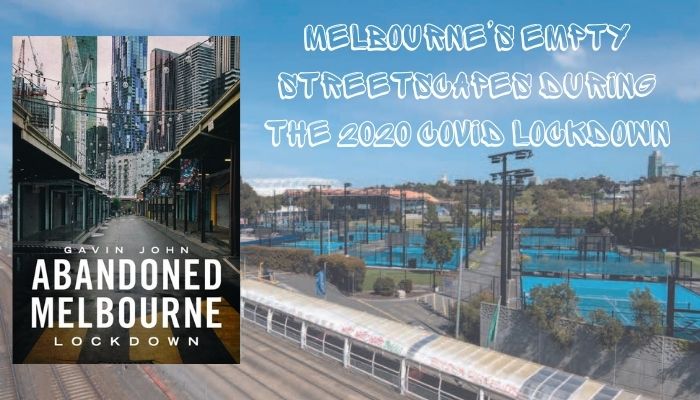

In a desire to keep working, and to accrue plenty of new images to work on while confined to the city (and probably to home), I committed to creating a body of work on a previously unseen ‘abandoned’ Melbourne. It seemed apparent that the 2020 pandemic could present the opportunity to contextualise the routinely thriving international city in this hitherto unseen way. Days before it looked like a full Wuhan-style lockdown would start, I seized the opportunity to head into what would prove to be an already desolate Melbourne, a city I’ve called home since the turn of century. The photographs featured in Abandoned Melbourne: Lockdown were captured in early March, with a few additions taken during the following months when opportunity and regulations allowed.

Melburnians have long understood the outstanding lifestyle opportunities on offer in their city. We self-appoint our city as the sporting capital of the world, with the Australian Open tennis grand slam, the Formula One Grand Prix and the Melbourne Cup being but a few of the annual tier one events on the sporting calendar. Melbourne also excels in art and culture with an abundance of galleries, museums, a thriving live music and festival scene and an astonishing array of dining out experiences. And good luck to anyone mounting an argument that Melbourne does not have the best coffee in the world. It’s not for nothing that Melbourne is consistently considered the world’s most liveable city.

So I set out to photograph a very different Melbourne from the one I had become accustomed to. This would be no reverie through inspiring landscapes, but an exploration into a very real-world crisis unfolding on my doorstep.

What would normally be a congested Saturday morning tram ride to the CBD was eerie. As the sole passenger I disembarked at the eastern end of Melbourne’s city centre with an eagerness that I might turn the negative of the pandemic to my advantage and finally photograph a city with the same elan as my landscape work. I improvised a route through the disconcertingly quiet city grid. Each scene laid out before me served to reinforce how seriously the citizens were already taking the pandemic. It was not quite yet officially lockdown, yet the place was deserted.

The civic buildings were all closed, the footpaths and streets lay empty, save for the odd rattling ‘ghost’ tram and a scattering of police cars. No wedding shoots setting up at the Treasury Building or Parliament House. No-one out buying coffee and doughnuts. Melburnians would come to crave doughnut days of a different kind, in fact double doughnut days – days with zero new infections and zero deaths. The city appeared like a Hollywood soundstage all prepared and awaiting call time for a hidden away cast. Instead of teaming with life and activity it seemed as if people had previously never been there, and that within the outré vistas lay treasures awaiting discovery.

It evoked memories of a past visit to the Angkor Wat temple complex in Cambodia, and I imagined the thoughts of naturalist Henri Mouhot who rediscovered the by then jungle-overrun development six centuries after its construction. Fortunately, the flora and fauna had not quite laid siege to the Melbourne architecture in a similar way just yet!

Many must-sees on any good tourist’s trip to Melbourne are depicted in the photographs contained in the book. Amongst them are Flinders Street Station, in the very heart of the city, and the National Gallery of Victoria, which usually surpasses the annual visitor numbers of Tate Britain and New York’s Guggenheim. The Burke Street Mall and Collins Street, two of the city’s busiest thoroughfares, are seen quiet and vacant. The magnificent Melbourne Cricket Ground lies dormant, and the surrounding sporting precincts, home to a cornucopia of world class sporting and entertainment events, show no hint of usual anticipatory crowds. Melbourne sports crowds are some of the most passionate and largest in the world. But they were silenced in 2020, just as Melbourne itself fell silent.

Professionally I am proud of the resulting photographs and the book, but the experience was also profoundly chilling and I fervently hope that the story the photographs tell will never be repeated.

Author: Gavin John